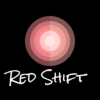

You have a delicate project, like crafting intricate wedding invitations or luxury packaging, but your laser cutter keeps scorching the paper. You're left with ugly, brown edges, wasted material, and a growing fear that your machine just isn't right for the job. The frustration mounts as every failed cut costs you time and money, putting your entire project at risk.

The key to cutting paper without burning is to vaporize the material so quickly that the surrounding fibers have no time to overheat and char. This is achieved by using a combination of very low power, extremely high speed, and a perfectly focused laser beam. Instead of burning through the paper, you are instantly sublimating it, turning the solid material directly into gas for a clean, crisp edge.

I remember working with a client who made high-end pop-up cards. They were struggling with brittle fold lines that would crack. They blamed their paper stock, but I suspected something else. We looked at their cuts under a microscope and saw microscopic charring deep within the paper fibers, even on cuts that looked clean to the naked eye. The issue wasn't just the visible brown edge; it was the unseen heat damage left behind. This experience taught me that a truly clean cut is about more than just appearances; it’s about preserving the material’s structural integrity.

What Settings Prevent Paper Edges from Turning Brown?

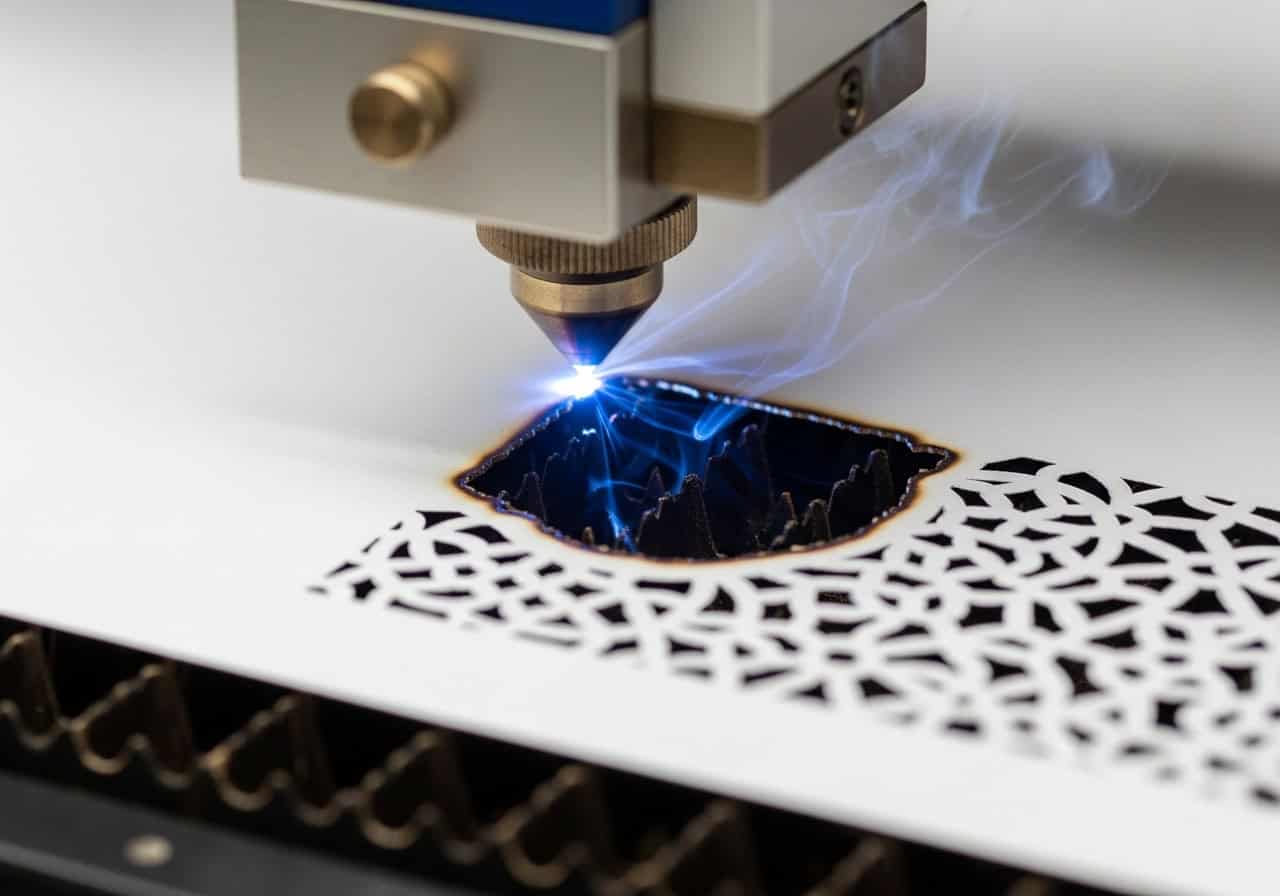

You're standing in front of your laser, ready to cut, but you hesitate over the controls. You know that the wrong combination of power and speed will turn your beautiful cardstock into a scorched mess. You run test after test, tweaking the settings, but you’re just guessing, wasting expensive paper and feeling like you’re flying blind.

To prevent brown edges, you need to use the lowest power setting possible combined with the highest speed your machine can accurately manage. The goal is to minimize the amount of thermal energy transferred to the paper. A fast-moving, low-power beam vaporizes the material in its path without lingering long enough to burn the surrounding fibers, resulting in a clean, color-free edge.

Simply saying "low power, high speed" is easy, but the reality is more nuanced. It’s a delicate balancing act that changes with every paper type.

1. Start with Speed

For thin materials like paper, your speed should almost always be maxed out. On most CO₂ lasers, this might be between 200 mm/s and 500 mm/s. A faster laser head gives the heat less time to spread. Running too slow is the number one cause of burning.

2. The Power Test

Once your speed is set to high, find your power setting. Start at the absolute minimum (e.g., 10%) and run a small test cut. Did it go through? If not, increase the power by just 1-2% and test again. Repeat this until the laser just barely cuts through the material. This is your sweet spot. The goal is to use zero excess energy.

3. Frequency (Hz) Matters

For more advanced RF lasers, you can also control the frequency (Hz), or how many times the laser pulses per second. For paper, a higher frequency (in the 5,000-25,000 Hz range) acts like a finer, sharper blade, delivering a smoother cut. Cheaper glass tube lasers don't offer this level of control.

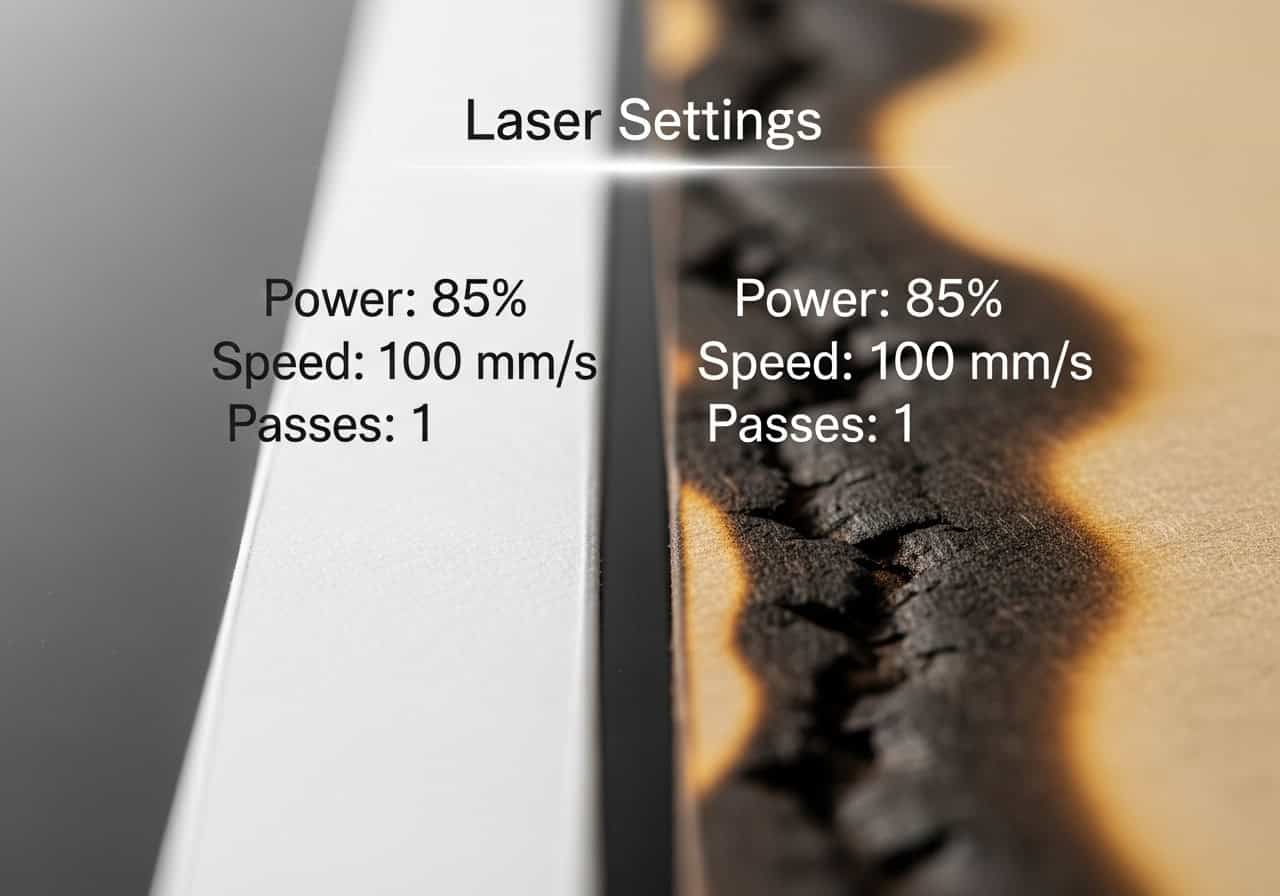

How Does Air Assist Boost Clean Cuts on Thin Paper?

You've dialed in your settings, but as the laser cuts, you see small flare-ups and smell burning. When the job is done, you find a sticky, resinous residue along the cut line and a slightly discolored edge. Your settings are right, so what’s still going wrong? You're frustrated that you can't achieve that perfectly clean result.

A strong stream of compressed air, known as air assist, is essential for clean paper cuts. It performs two critical jobs at once: it blows away vaporized paper particles and combustible gases before they can ignite (preventing flare-ups), and it instantly cools the cut edge. This cooling action is vital for preventing heat from soaking into the surrounding paper fibers and causing them to turn brown.

Air assist isn't just a fan; it's a high-pressure, focused tool. Optimizing it is crucial for delicate work.

1. Pressure and Flow

For paper, you don't want a hurricane of air, which could tear or move the delicate material. You need a moderate, consistent pressure (around 15-20 PSI). The goal is to create a clean, localized jet that clears the kerf (the cut line) efficiently without disturbing the rest of the sheet.

2. Clearing Debris vs. Cooling

The air stream's primary job is to get vaporized particles out of the way. If these particles linger, the laser beam will hit them again, superheating them and causing the smoke and residue that stains the paper. The secondary cooling effect is a bonus that further helps prevent browning.

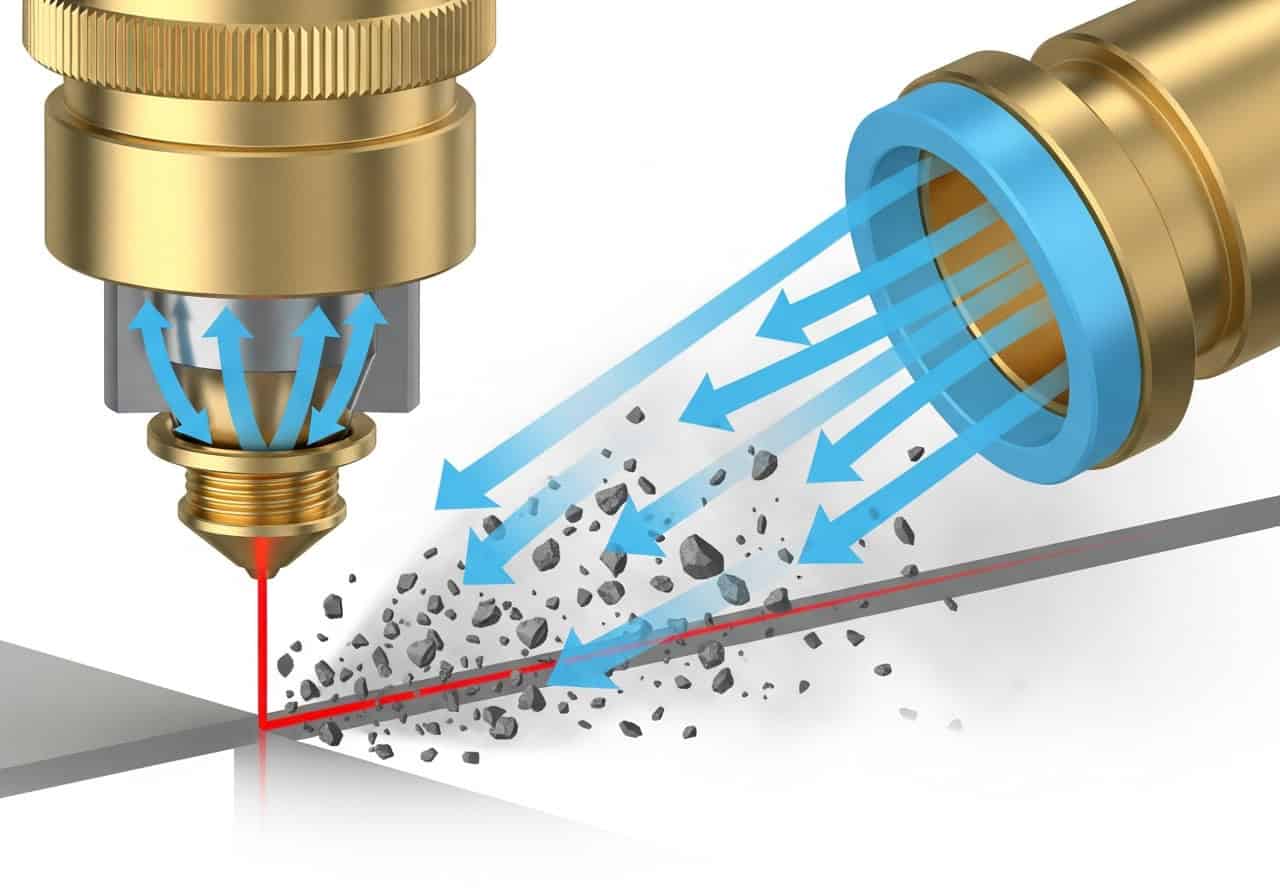

3. Nozzle Choice

The nozzle at the end of your laser head focuses the air stream. A smaller, conical nozzle creates a more powerful, pinpoint jet of air. This is ideal for paper because it concentrates the clearing and cooling effects directly at the point of the cut, providing maximum efficiency without blowing your lightweight material all over the laser bed.

Can Different Paper Types Handle CO₂ Lasers Differently?

You perfected your settings on a standard piece of cardstock, achieving beautiful, clean cuts. But when you switch to a glossy, coated paper or a fibrous, handmade stock for a new project, everything changes. The same settings now produce burning, melting, or incomplete cuts, forcing you to start your frustrating trial-and-error process all over again.

Yes, every paper reacts differently to a CO₂ laser due to its unique density, fiber content, and chemical coatings. A dense, high-quality cardstock will absorb heat evenly and cut cleanly. A loose, fibrous paper is more prone to charring, while a glossy or plastic-coated paper may melt and leave a hard, beaded edge. Each type requires its own unique "sweet spot" of power and speed settings.

Understanding the material is half the battle. You aren’t just cutting "paper"; you are cutting a specific composite of fibers, binders, and coatings.

1. Fiber Content and Density

Papers with tightly packed, uniform fibers (like high-grade cardstock) tend to cut best. They vaporize cleanly. Papers with loose, airy fibers (like cheap construction paper or some recycled stocks) have more oxygen pockets and are more likely to smolder and char.

2. Binders and Coatings

Many papers contain binders, glues, or clays to give them a smooth, glossy finish. These additives react to heat differently than cellulose fiber. Glossy coatings can melt into a hard, plastic-like bead along the cut edge, while certain binders can cause discoloration.

3. The Unseen Enemy: Moisture Content

Paper is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs moisture from the air. A sheet of paper in a humid workshop will contain more water than one in a dry environment. This moisture must be boiled off by the laser before it can cut the fibers, requiring more energy and increasing the risk of heat-related damage.

| Paper Type | Common Reaction | Pro Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Matte Cardstock | Cuts cleanly | The ideal material. Easy to dial in settings. |

| Glossy/Coated Paper | Melting, hard edges | Use masking tape to protect the surface and reduce melting. |

| Fibrous/Handmade | Charring, flare-ups | Maximize air assist and speed to blow out embers. |

| Corrugated Cardboard | High risk of fire | Requires high air assist and constant supervision. |

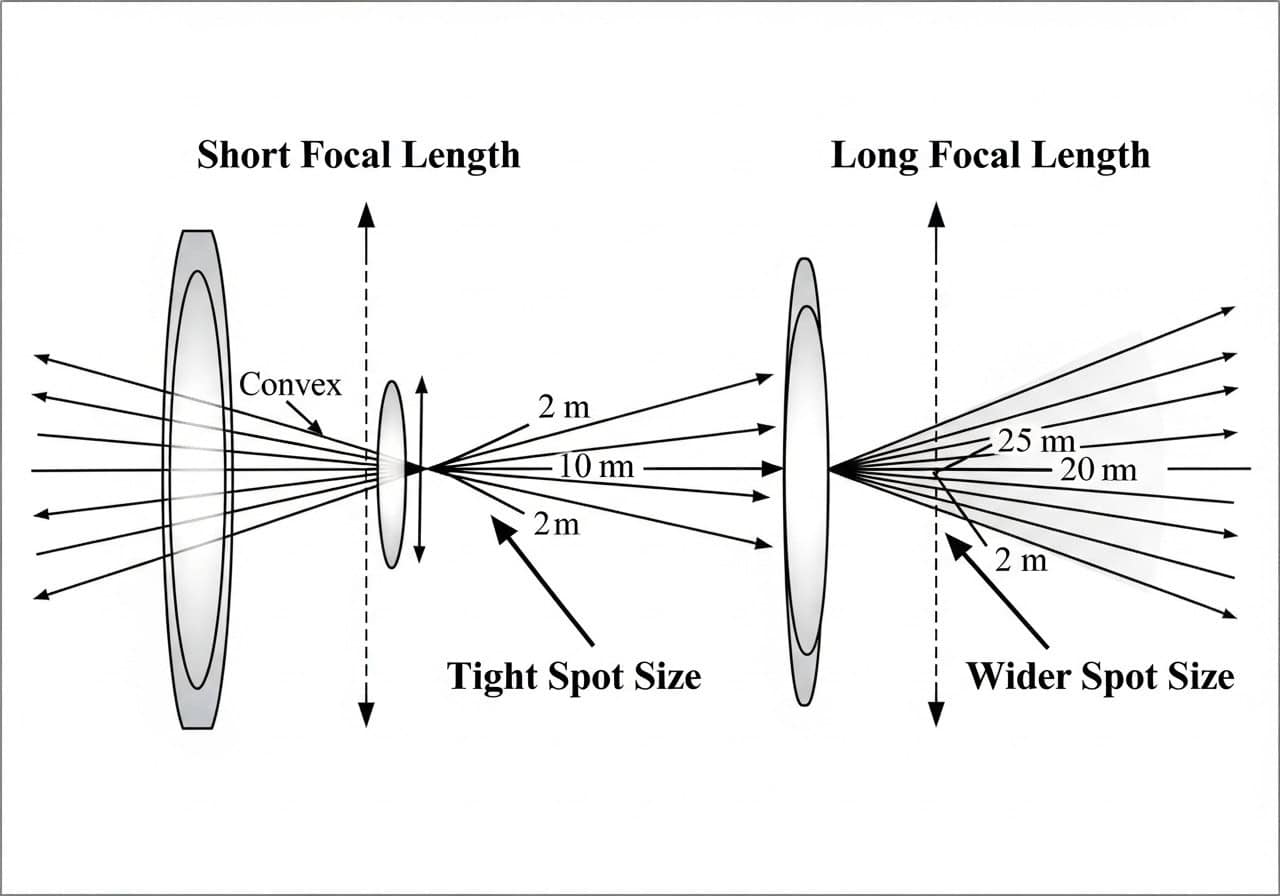

Why Does Laser Focal Length Matter for Delicate Materials?

You’ve mastered your power and speed settings, but your cuts still aren't as sharp as they could be. You notice that very fine details are getting blurred, and the cut line (kerf) is wider than you want. You're getting clean cuts, but you're losing the ultra-fine precision that your high-end project demands.

Focal length determines the size and intensity of the laser's focal point, which is critical for delicate materials. A shorter focal length lens (e.g., 1.5 inches) creates a smaller, more intense spot size. This allows you to cut with a thinner line (a smaller kerf) and a lower power setting, which imparts less overall heat into the paper and preserves fine details.

This is where we separate a good operator from a great one. The real enemy isn't brown edges; it's the invisible damage from latent heat.

1. The Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ)

Even a visually perfect cut leaves behind a "Heat-Affected Zone" or HAZ. This is a microscopic area where the paper fibers, while not burnt, were heated enough to become brittle. This is the real manufacturing challenge. For luxury packaging or pop-up cards, this brittleness leads to cracking along fold lines, causing product failure days or weeks after the cut was made.

2. The Illusion of "Low and Slow" vs. "Fast and Furious"

Many operators think lowering power is the only answer. But the real secret is delivering that energy in a much smarter way. You need to hit the material with an intense burst of energy that vaporizes it instantly, before the heat has time to soak into the surrounding material and create a large HAZ. It's a thermodynamic race.

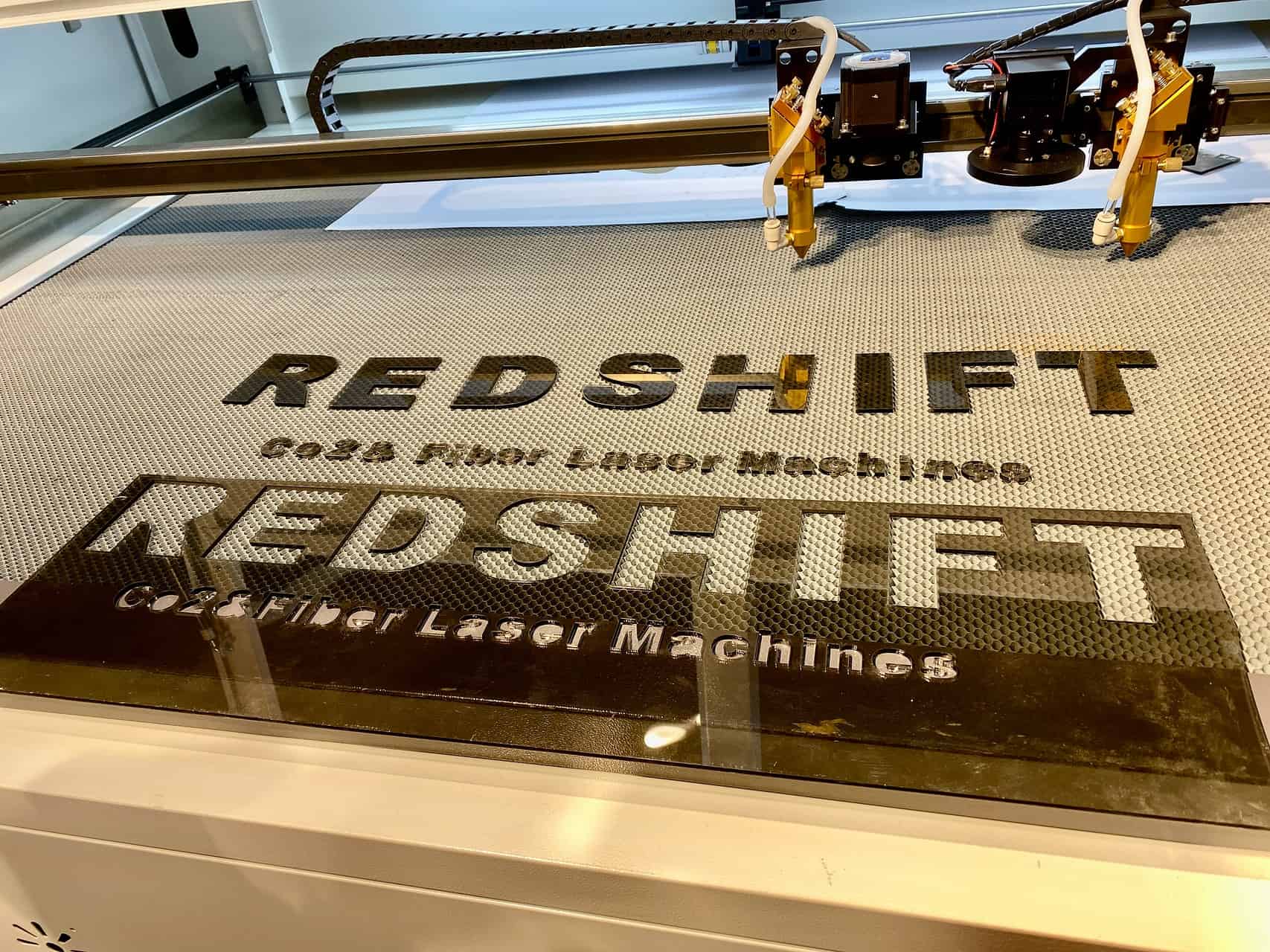

3. RF-Excited vs. Glass Tube Lasers

This is where the type of laser source becomes critical. Cheaper glass-tube CO₂ lasers1 have a slower "pulse" response. They are good at delivering a steady stream of energy. However, higher-end RF-excited metal tube lasers can be pulsed thousands of times per second with extremely fast rise and fall times. They can deliver those short, sharp, high-peak-power bursts needed to win the race against heat transfer. This is how you minimize the HAZ2 and create cuts that are not only clean but also strong and flexible.

Conclusion

Cutting paper on a CO₂ laser without burning is a process of mastering heat control. While basic settings like low power and high speed are the starting point, true manufacturing excellence comes from a deeper understanding. By optimizing air assist, respecting the unique properties of each paper type, and using the correct focal length, you gain more control. Ultimately, the goal is not just to avoid brown edges, but to minimize the invisible Heat-Affected Zone by delivering energy quickly and efficiently, a task where RF-excited lasers excel, ensuring your final products are both beautiful and durable.

FAQ

Q1: What is a good "rule of thumb" for finding the right laser settings for a new type of paper?

A: Use the "test grid" method. Create a grid of small squares in your laser software. Assign a different power level to each row (e.g., 10%, 12%, 14%) and a different speed to each column (e.g., 200mm/s, 250mm/s, 300mm/s). Run this grid on a scrap piece of the new paper. The square that cuts through completely with the least amount of browning reveals your ideal starting point.

Q2: I've lowered my power and increased speed, but I still see slight browning. What's the next step?

A: Check your air assist and focus. A weak or unfocused air stream fails to clear debris and cool the edge effectively. Also, perform a ramp test to ensure your laser is perfectly focused. An out-of-focus beam is wider and "cooks" the paper rather than vaporizing it, causing browning even at high speeds.

Q3: My air assist is on, but it's blowing my lightweight paper around. How do I fix this?

A: You likely have too much pressure, or your paper isn't secured. First, try reducing the air pressure (PSI) to a level that clears debris without acting like a leaf blower. Second, use a honeycomb bed with honeycomb pins or small, powerful magnets (placed carefully away from the laser path) to hold the paper flat and secure against the bed.

Q4: How can I minimize the risk of fire when laser cutting paper?

A: Never leave the machine unattended. Ensure your air assist is always on and functioning correctly, as it extinguishes flare-ups. Keep your machine's exhaust system clean for proper ventilation and remove all scrap paper pieces from the laser bed between jobs to eliminate fuel sources. Having a CO₂ fire extinguisher nearby is standard safety protocol.

Q5: You mentioned the "Heat-Affected Zone" (HAZ). How can I test if my paper is brittle even if it looks clean?

A: The "fold test" is the easiest way. Take a piece of paper that you've cut and gently fold it along the cut edge. Then, fold it back and forth a few times. If the paper has a minimal HAZ, it will feel like a normal folded edge. If it's brittle due to heat damage, it will crack, tear, or snap cleanly along the cut line with very little effort.

Q6: My laser isn't cutting completely through the paper, but increasing the power causes burning. What's wrong?

A: This classic dilemma is almost always a speed or focus issue. Your speed is likely too high for the power you're using. Instead of increasing power, try decreasing your speed in small increments (e.g., from 300mm/s to 280mm/s). This gives the beam slightly more time to cut through without adding enough thermal energy to cause burning. Also, re-check your focus.

Q7: The article's table mentioned masking tape. When and why should I use it on paper?

A: Use transfer or masking tape on papers that are prone to surface staining from smoke and debris, especially resinous or fibrous stocks. The tape acts as a sacrificial layer. The laser cuts through it, but any smoke or residue settles on the tape's surface. When you peel the tape off, you get a pristine, clean surface around the cut.

Q8: For cutting intricate paper designs, is a shorter focal length lens always better?

A: Generally, yes. A shorter focal length lens (like 1.5" or 2.0") produces a smaller spot size and a narrower kerf (cut width), allowing for finer detail. However, it also has a shorter depth of focus, meaning the material must be perfectly flat. For slightly warped or thicker paper-based materials like cardboard, a standard 2.5" lens might be more forgiving.

Q9: Why does glossy or coated paper melt, and how do I prevent the hard, beaded edge?

A: The glossy coating is often a thin layer of plastic, clay, or polymer. Instead of vaporizing like paper fiber, it melts under the laser's heat and re-solidifies into a hard bead. To prevent this, use the absolute lowest power that will pierce the material, combined with maximum speed and very strong air assist to "freeze" the edge before it can form a bead. Masking can also help dissipate some surface heat.

Q10: Can I still achieve professional, non-brittle results with a standard glass tube CO2 laser?

A: Yes, you can achieve visually clean cuts with a glass tube laser by carefully balancing your settings and maximizing your air assist. However, minimizing the invisible brittleness from the HAZ is much harder. An RF-excited laser's ability to deliver rapid, high-peak-power pulses is scientifically better at winning the race against heat transfer, making it the superior choice for high-end applications where material integrity (like on a fold line) is non-negotiable.